A garden for peace This garden is dedicated to peace. To the women and men who - individually or together - have envisioned, built, and nurtured paths of peace in defense of human rights and human dignity. Here we remember just a few examples - those who, often at great cost, opened new ways and pointed toward new directions. Let us not be discouraged. Until peace and justice belong to all. |  |

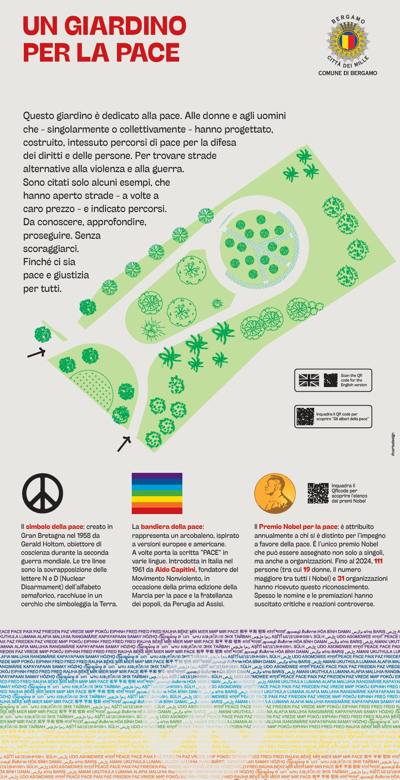

Bertha Von Suttner The First Woman to Receive the Nobel Peace Prize An Austrian writer, Bertha von Suttner is best known for her major work Lay Down Your Arms, published in 1889 and translated into over 20 languages. In 1905, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, thanks in part to the support of her great friend and admirer Alfred Nobel. She spoke out against the militarization of China and the development of aircraft for warfare. In August 1913, already seriously ill, she attended the International Peace Conference in The Hague, where she was named "Generalissimo" of the international peace movement. Women at the Front Lines of Peace. Here are just a few:

|  |

Mahatma Gandhi Nonviolence as a Method for Resolving Conflict The idea of civil disobedience was first developed in the United States in the 19th century by Henry David Thoreau, who was jailed for refusing to pay taxes in protest against slavery and war. But it was Mahatma Gandhi who brought theory and practice together. One of the most iconic examples was the Salt March of 1930. With thousands of followers, Gandhi walked over 300 kilometers to the sea to symbolically break the British monopoly on salt production. Gandhi’s philosophy inspired major global figures such as:

In Italy, Danilo Dolci and Aldo Capitini embraced nonviolence to promote justice and peace. |  |

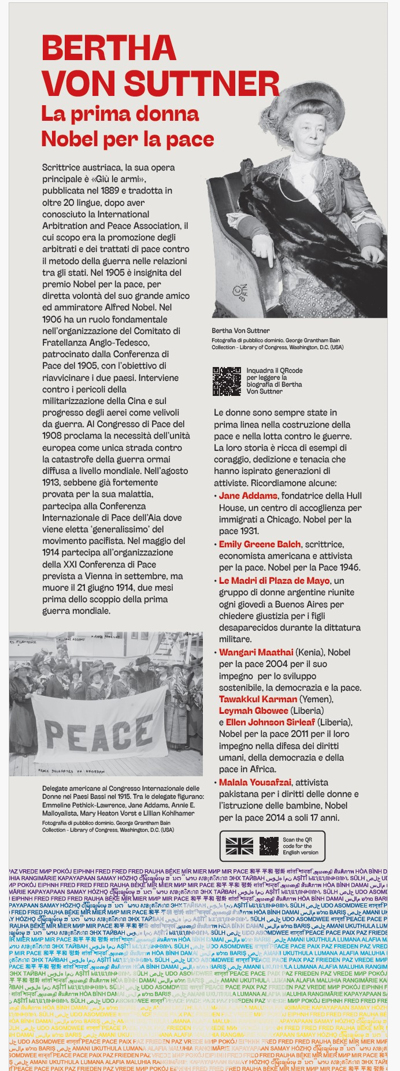

From war to hope The United Nations and Nelson Mandela The process leading to the foundation of the United Nations began at the end of World War II, which shook the entire planet. The UN’s goals are to maintain international peace and security, protect human rights, provide humanitarian aid, promote sustainable development, and uphold international law. From the Gulf War in 1991 to more recent conflicts, the UN has often proven powerless, hindered by the interests of powerful nations and blocs. Nelson Mandela was a long-time leader of the South African anti-apartheid movement, including through armed struggle, and played a decisive role in ending the segregationist regime, despite spending 27 years in prison. As South Africa’s first non-white president, Mandela worked with his predecessor Frederik de Klerk to dismantle apartheid; both were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. As president, Mandela led the transition from the old regime to democracy, earning worldwide respect for his support of national and international reconciliation. |  |

The Italian Constitution repudiates war The Constitution’s Commitment to Peace The terrible war from which Italy emerged in 1945 inspired the country’s founding fathers and mothers to firmly vow never to allow such horrors to happen again. At the same time, the defense of the homeland - even by force - is declared a “sacred duty of the citizen” (Article 52). To build a peaceful world, the Constitution encourages Italy to enter into agreements and form organizations with other countries - such as the United Nations and the European Union - even if this means accepting a reduction in “sovereignty.” Following the Constitution, important laws were enacted as the result of public awareness and mobilization: recognition of conscientious objection and civil service, the establishment of voluntary peace corps, and international cooperation initiatives. The state’s efforts have been joined by local authorities, in a “bottom-up diplomacy” masterfully practiced by the mayor of Florence, Giorgio La Pira, and by civil society, committed to weaving threads of peace both inside and beyond national borders. In this effort, educating younger generations about peace plays a fundamental role. Military Spending Global military spending reached a record $2.443 trillion in 2023, a 6.8% increase compared to 2022. |  |

Pope John XXIII addresses Pacem in Terris to all people of good will With the encyclical “Pacem in Terris” dated April 11, 1963, Pope John XXIII clearly positioned the Catholic Church on the side of peace. Recalling the words of Pope Pius XII - “Nothing is lost through peace; everything may be lost through war” - John XXIII hoped that nations possessing lethal weapons would avoid the “unpredictable and uncontrollable” event of a new war. War, peace, and the protection of creation are therefore vital elements in humanity’s journey. In the encyclical, the Pope addressed, for the first time, “all people of good will,” believers and non-believers alike, because the Church must look towards a world without borders or “blocks” and does not belong to the West or the East. “Pacem in Terris” is not an “utopian or culturally neutral message,” but a message of hope to fight the fear of the future, and it remains an invaluable ethical and cultural heritage. The spirit of the Second Vatican Council, opened by John XXIII, embraced and strengthened this call for peace coming from both the secular and Catholic worlds. |  |

There is no peace without recognition of rights Twenty-seven million people live in slavery - more than double the number during the peak of the slave trade. Where individual and group rights are trampled, there can be no peace. Peace is not merely the absence of war, but a responsible coexistence of different rights, needs, and interests. Throughout history and across the world, conflicts have been and continue to be countless because humanity is not a homogeneous or unified whole. Those resolved through nonviolent methods pave the way for peaceful coexistence. In these movements, women, men, and organizations have often risked their freedom and lives for the future of humanity. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on December 10, 1948, established for the first time the fundamental human rights to be universally protected for all people, regardless of race, color, religion, sex, language, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, or other status. Without recognition of rights, there can be no peace. |  |

There is no peace without social justice and environmental protection The Commitment to Social Justice is essential for building peace. Work is a fundamental part of life, where people use their skills, express themselves, gain independence, and contribute to the common good. But too often, profit and the market seem to be the only guiding principles. If there is no work, or if work is precarious, threatened, or lacks dignity, there is no peace. If a land’s natural resources are exploited by a few or by foreign powers, there is no peace. If a person must seek job opportunities and personal growth in another country, there is no peace. Where there is poverty, neglect, and abandonment… there is no peace. In his encyclical Laudato si’, Pope Francis promotes the vision of integral ecology, which links the growing environmental problems (global warming, pollution, resource depletion, deforestation, etc.) with social issues: “There are not two separate crises, one environmental and one social, but one complex socio-environmental crisis.” The solutions require an integrated approach to fight poverty, restore dignity to the excluded, and care for nature. In other words, “we cannot ignore that a true ecological approach is always a social approach that must integrate justice into environmental discussions, listening to both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor.” Peacebuilders are those who defend workers’ rights - especially where they are denied - as well as those who protect environmental biodiversity and safeguard it for future generations. In many countries, even today, environmental defenders risk their lives for their commitment. |  |